Oliver Wainwright, The Guardian, July 22, 2015

Parked like a red brick aircraft-carrier in the leafy suburbs of Buffalo, New York, stands the most opulent private house that Frank Lloyd Wright ever built. Its 400 windows sparkle with intricate art-glass panels, the mortar between its bricks gleams with gold, while its rooms are lined with eight miles of wooden panelling and thousands of hand-glazed mosaic tiles. It was “the most perfect thing of its kind in the world”, Wright said, with characteristic modesty, “a domestic symphony” that was the ultimate“opus” of his Prairie house style.

‘A domestic symphony’ … inside the Martin House by Frank Lloyd Wright

“It was extravagant beyond all reason,” is how Mary Roberts puts it. As the director of the Martin House Restoration Corporation, which has spent the last two decades and $50m doing up the building after years of neglect, she knows quite how much excess Wright lavished on the commission. “Just one of these windows costs $28,000 to reproduce,” she says, wrenching open one of the panes, inlaid with Wright’s trademark tree of life design.

Completed in 1905, it was a fitting monument to one of the most successful businessmen in the city, Darwin D Martin, an executive of the Larkin Soap Company, which pioneered mail-order sales and built one of the most revolutionary office buildings of all time, also designed by Wright.

Across town, a small brick stump is all that remains of the Larkin administration building, after it was demolished in the 1950s, but it is a site that nonetheless attracts architectural pilgrims to come and worship. “It rewrote every rule of the office,” says Tim Tielman, when we meet at the hallowed stump. “It introduced air conditioning, gravity heating, toilets hung from the wall – and Wright designed every last detail, including all the furniture. He was a maniac.” An architectural historian who has spent a lifetime battling to save Buffalo’s built heritage, Tielman says he knows where the remains of the Larkin building are buried: dumped in the Ohio canal basin, beneath what is now a park. “One day we’ll dig it all up and rebuild it,” he says, almost popping with excitement. “It’s not a question of if – but when.”

Opulent … the (unfinished) Darwin D Martin House restoration, Buffalo, New York. Photograph: Philip Scalia /Alamy

He is not the only person in Buffalo who has ambitions to raise Wright’s designs from the dead. The diminutive cape-wearing architect built a handful of houses here during his 30-year association with the city, but he’s recently been enjoying a flurry of posthumous commissions, more than half a century after his death.

A few blocks away stands a mysterious pink pavilion. This is Wright’s design for a filling station, which lay tucked away in a drawer until last year. “Wright demanded a fee that was the same as the cost of building the damned thing,” says James Sandoro, the 70-year-old owner of the Pierce-Arrow transport museum, who has spent $1m realising Wright’s unbuilt paean to the new car culture of the roaring 20s (and a further $10m on a giant shed in which to house it). “It probably didn’t help that he wanted to have open fires beneath the gas tanks in the roof.”

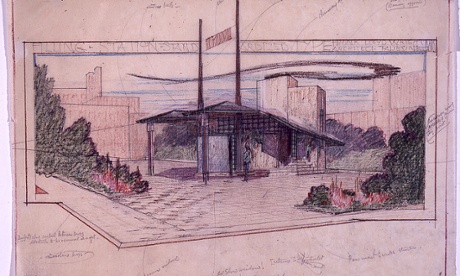

Sketch for Filling Station, Buffalo, by Frank Lloyd Wright

Ever the innovator, Wright had proposed a gravity-fed pumping system, where the petrol would flow down from the roof through dangling pipes, in patriotic red, white and blue. But he also insisted on having an open hearth down below, to give the attendant’s quarters a domestic touch. “Everything he built was dangerous,” says Sandoro, tiptoeing past the steep staircase that leads to the basement, roped off for safety reasons.

Like some kind of steampunk flying machine, the building extends two long copper wings out above the salmon-coloured concrete base, pierced by two 14-metre-high totem poles. Wright’s sketches show the copper a rich green verdigris, a colour picked up in the window frames, but Sandoro has left it gleaming in mirror-polished pink.

“It’s not outside, so it’s not going to go green,” he says, matter-of-factly. It’s the same reason he didn’t include glass in the window frames, which he’s made in wood rather than the intended metal. “It’s a museum piece and we’re not pretending otherwise.” It is little more than a stage-set, a flimsy Wright-themed billboard, but Sandoro says museum visitor figures have increased fivefold since it opened.

And in reality … James Sandoro’s Filling Station, Buffalo

Ten minutes’ drive northwest, on edge of the city where Lake Eerie feeds into the Niagara river, stands another recently resurrected Wright design, built to be anything but a museum piece. “This is a building that’s designed to be used,” says Olivia McCarthy, opening the double-height oak doors of the Fontana Boathouse, to reveal racks piled high with fibreglass hulls. Wright designed it in 1905 for the University of Wisconsin rowing club, 700 miles away, but it was finally built here in Buffalo in 2007.

Wright would have gone crazy if he’d seen this stuff. He'd say why take a design that’s 100 years old and build it now?

Perched on the water’s edge like an austere concrete bunker, it looks as stark now as the day it was published in the Wasmuth Portfolio, the volume of Wright’s drawings printed in Berlin in 1911 that made his name internationally. Legend has it that Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius (who were all working as apprentices in the same office at the time) stopped work for the day when the portfolio arrived, to pore over the dazzling designs of the American maestro.

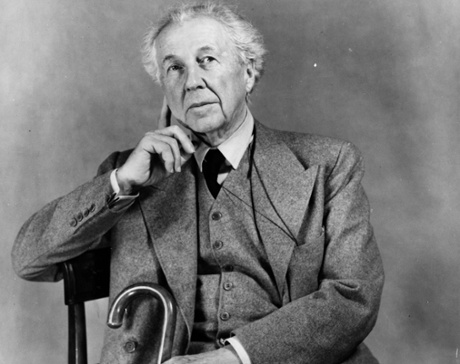

Assured of his own genius … American architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959)

It is unlikely they would be quite so enamoured if they saw what’s been built in Wright’s name a century later. Like the gas station, the boathouse stands up from a distance, but get close and it feels like a scale model that’s been enlarged. Wright only produced two small drawings of the building, so there’s been a lot of guesswork. Modern regulations mean that the balcony parapet wall has an extra glass guardrail fixed on top, while the windows have a stick-on diamond leading effect.

“It can never be an exact historic reproduction,” says Anthony Puttnam, the 81-year-old architect and former student of Wright’s who was charged with interpreting the plans. “It’s a working boathouse that carries Mr Wright’s spirit. I’m sure he would have had plenty to say about what we’ve done wrong. But I can guarantee he would have wanted these buildings built – he thought they were very good. And he intended his unbuilt projects to be a source of income for the foundation and the school.”

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, based at Wright’s school in Taliesin West in Arizona, is known for its fierce guardianship of the architect’s intellectual property, which has become a lucrative money-earner, comprising an empire of over 1,500 licensed products. The boat club paid $80,000 to the foundation for the rights to build the design, while Sandoro says it cost him $175,000 for the gas station plans. Others who’ve tried to build without their blessing have felt the wrath of Wright’s ghost in the courts.

Sketch for the Blue Sky Mausoleum

“For a long time, there was a whole host of people who were basically feeding at the trough of the Frank Lloyd Wright name,” says Philip Allsopp, president of the foundation from 2006-9, who finally put a stop to the practice of rebuilding Wright’s unrealised designs, of which there are still almost 500 in the archive. There was an increasing number of enquiries to raid the back catalogue after a series of posthumous houses appeared in the early 2000s, from a villa on an island in New York state to one in County Wicklow in Ireland, as well as a recent attempt to build one of his Californian house designs in a field in Somerset, which hit the buffers of local planning policy.

“Wright would have gone crazy if he’d seen this stuff,” says Allsopp. “His buildings were designed for their specific sites and contexts, and he was perpetually pushing the envelope. He’d be saying ‘Why take a design that’s a hundred years old and build it now?’”

Perhaps the most fitting zombie design to stagger out from Wright’s grave is to be found in Buffalo’s Forest Lawn cemetery, where the grand mausoleum he designed for Darwin Martin and his family now stands. Designed in 1928, on the eve of the stock market crash that would obliterate Martin’s fortune (and the project with it), it was a radical scheme that fused “the grave and the mausoleum, [with] the better points of both”, according to Wright.

And today’s version … the Blue Sky Mausoleum

Built in bright white granite, shallow stone steps, covering 24 crypts rise from the edge of a lake up to a monolith, flanked by a bench on either side and inscribed with Wright’s own high opinion of his design: “The whole could not fail of noble effect.”

Not everyone agrees. “A lot of visitors ask when it’s going to be finished,” chuckles the cemetery’s programme director, Sandy Starks. Completed in 2004, only three of its crypts have been sold so far, despite the lure of a limited-edition Wright-themed glass sculpture that comes free with signing up for a place in the tomb. He may be long dead, but the man and his merchandise are still going for the hard sell.

- All Wright All Day tours run throughout the summer, including stops at all the major Frank Lloyd Wright sites in Buffalo.

This article originally appeared on guardian.co.uk

This article was written by Oliver Wainwright in Buffalo from The Guardian and was legally licensed through the NewsCred publisher network.

![]()