Rachel Cooke, The Guardian, July 20, 2015

Two Fishes, 1948 by William Gear. Photograph: Copyright the Artist's Estate. Image courtesy of lender

In 1958, the artist William Gear arrived in Eastbourne to take up a position as curator of the Towner Gallery. Alas, not everyone was thrilled by his arrival, at least not after he began acquiring art on the town’s behalf. “I think this sort of painting is decadent,” lamented an enraged councillor of Harold Mockford’s Eastbourne (1958), a landscape some likened to a snow-covered slag heap. “Any artist with anything about him at all could do that in two hours.”

In 1959, when Gear mounted an exhibition called English Contemporary Art, a letter to the local paper complained that “such daubs must have been painted by persons with very depraved minds”. Did he imagine any right-thinking citizen of Eastbourne wanted to look at the efforts of a bunch of “teddy boys”?

But Gear was not to be put off: the son of a Fife coal miner, he carried with him a streak of stubbornness as wide as the Grand hotel. During the next six years, his acquisitions would include works by Sandra Blow, Edward Burra, Alan Davie, Patrick Heron, Roger Hilton, Peter Lanyon and Edward Wadsworth: a vibrant collection that, as the Observer noted in 1962, contributed magnificently to the Towner’s growing reputation as the “most go-ahead municipal gallery of its size in the country”. Only in 1964, when Gear was appointed head of the Faculty of Fine Art at Birmingham College of Art, did he resign, by which time his work was done. The town now had the foundations of a collection of 20th-century British art of which it would one day be rather proud.

‘Unyielding angles’: a William Gear self-portrait from 1949. Photograph: Copyright the Artist's Estate. Image courtesy Fosse Gallery

At the Towner Gallery, two exhibitions tell William Gear’s unlikely story. The first, A Radical View, focuses on his six-year stint as its curator, complete with yellowing newspaper cuttings and frothing-at-the-mouth letters to the editor. The second, William Gear 1915-1997: The Painter That Britain Forgot, is a show of 100 of his own paintings and prints. Each show is fascinating in its own right, but together they make for a deeply satisfying dialogue: see Gear’s work and you better understand the engine of his conviction that British galleries needed desperately to modernise, to look beyond their stuffy Victorians and into the future. Consider the various artists he promoted during his curatorial career and you have a more complete grasp of his infatuation with abstraction.

Both shows also betray Gear’s somewhat obdurate nature. If his application to the Gulbenkian Foundation for a grant reveals a man reluctant to do anything by committee (an award would enable him to bypass his windy alderman enemies altogether), his self-portraits, flat-capped and narrow-eyed, reduce him to a series of unyielding angles.

Gear is little known now but in his time he was a controversial artist whose work frequently found its way into our national collections (The Painter That Britain Forgot includes loans from Tate and the National Gallery of Scotland). After studying at the Edinburgh College of Art in the 30s – he was, a fellow student recalled, “alone amongst his peers in pursuing his own work to the point of pure abstraction” – he travelled through Europe on a scholarship and the world tilted excitingly. In Paris, he saw Picasso’s Guernica and studied under Fernand Léger. In Turkey, he was able to visit the Byzantine mosaics he’d long loved from afar. In 1940, he was called up and posted to the Middle East, where he continued to work as an artist, making good use of any spare vehicle paint. After VE Day, he moved to Berlin, where he became a “Monuments Man”.

The war over, he returned to Paris. There, a dealer who saw an exhibition of his work invited him to do a solo show in London (curator David Sylvester would describe him as “one of our few real colourists – makers not of pattern but of light”). But for Gear, Britain was hardly the centre of the universe. Invited to St Ives by Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, with whom he’d studied in Edinburgh, he was repulsed by what he saw as its provincialism: “I was a Parisian now… it was pretty small beer to me.”

In 1949, moreover, he would appear alongside other CoBrA artists – supposedly the European answer to American abstract expressionism – at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (he also showed with Jackson Pollock in New York, though the name then meant nothing to him). Nevertheless, in 1950 he returned home, moving with his American wife to a cottage in Buckinghamshire. Responding to an Arts Council invitation to create a work for its Sixty Paintings for ’51 show, he produced the hefty Autumn Landscape.

Broken Yellow, 1967: ‘a kaleidoscopic explosion’. Photograph: The artist's estate, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

When it was awarded a Festival of Britain purchase prize of £500, there was a terrible fuss. Why, the chancellor, Hugh Gaitskell, was asked, was a hard-pressed nation wasting its money on this rubbish? This debate, for all that Gear disdained it, made him famous.

William Gear: The Painter That Britain Forgot takes a roughly chronological approach to his career. Early on, however, the visitor gets the chance to look ahead; through a specially constructed “window”, one can see the vast Autumn Landscape in all its glory. Its shades are brown, yellow and red – an “equivalence” of autumn, as Gear put it – but its piled angles refer back to the destruction of the war, and beyond that to Gear’s childhood, to the pithead and its winding gear. On the part of the curators, this preview, glimpsed from the exhibition’s first room, is a smart move: for the visitor trapped bemusedly among the highly derivative work of a painter struggling under the influence of Léger, Matisse, Braque, Dufy and Klee, it provides a good reason to press on.

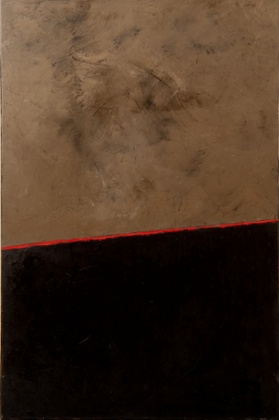

Winter Landscape, 1955. Photograph: Copyright the Artist's Estate; image courtesy Jerwood Gallery

Gear is best known (where he’s known at all) for his large, colourful canvases, oils that often seem to have been painted beneath stained glass on a sunny day, their jewel-like shards outlined in oppressive black; the biggest of these is Broken Yellow, a kaleidoscopic explosion from 1967 of orange, yellow and black, whose eruptive patterning falls somewhere between Klimt and a certain kind of studio pottery.

But the best of his works, it seems to me, are far quieter. Winter Landscape (1955) comprises a burnished sky, a fiery orange line where the horizon should be and a black hill rising darkly to meet it. White Square (1956) is a rectangle of blue-grey on charcoal stripes that might, according to your mood, be a window or a memorial stone. In Black Square, Green Bar (1957), the two elements of its title are arranged on a textured background of dirty pink; it as if they have unaccountably been left out in the rain and their darker colours have run.

Why has Gear been forgotten? The curators speculate that his relative obscurity can be traced to his solitary nature as an artist, to his reluctance to join any school. But perhaps it’s more straightforward than this, a matter less of jinxed fame – of his having failed, in effect, to find safety in numbers – than of simple confidence. Even as you salute the cosmopolitan sensibility that seems so at odds with the cardigan and tie in which he worked, it’s impossible not to notice that the pictures with which he made his name often feel effortfully second hand. Lucky, then, that this show is so extensive, for it’s on the many less attention-seeking of his paintings that the 21st-century eye will undoubtedly want to linger.

- A Radical View: William Gear as Curator 1958-64 is at Towner, Eastbourne until 31 Aug; William Gear 1915-97: The Painter That Britain Forgot runs until 27 Sept

This article originally appeared on guardian.co.uk

This article was written by Rachel Cooke from The Guardian and was legally licensed through the NewsCred publisher network.

![]()